The Wabanaki Forest

By Rebecca Jacobs, Posted on October 26, 2021

You may have noticed that over the past year, we have begun to refer to the forest in the Maritimes as the Wabanaki-Acadian Forest, or simply the Wabanaki Forest. You may be wondering where this name comes from or why we’ve made this change.

In Canada, climate justice cannot be separated from Indigenous reconciliation and the work of decolonization. That is why Community Forests International is continually learning ways to centre Indigenous justice within our work to protect and restore these special forests — all while working to deepen our partnerships with Indigenous Nations, organizations, and communities.

“New Brunswick is unceded, unsurrendered territory. So when we talk about the natural forest, it’s the Wabanaki forest. It’s not the Acadian forest.”

Steve Ginnish, Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn Inc.

Language has been and continues to be used as a tool of colonization–but language can also be a tool for reconciliation. Using Indigenous place names is one way in which Indigenous peoples are reclaiming the land from settler states— and is a way all people can honour the land and the Indigenous Nations who have called it home since time immemorial.

What does Wabanaki mean?

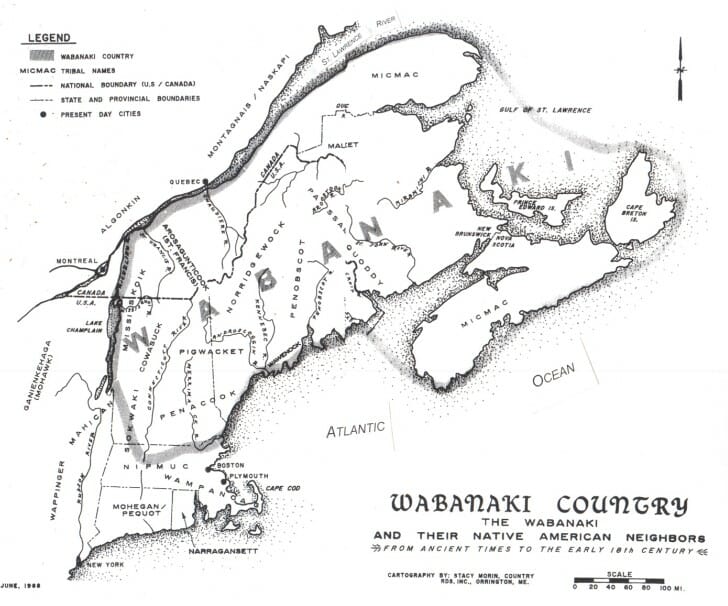

Wabanaki comes from the Algonquian word Wabanakik, meaning “Dawnland”, and stems from waban (meaning “light” or “white,” referring to the dawn in the east), and aki (“land”). The Wabanakik region roughly spans the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and parts of New England. Wabanaki (“People of the Dawnland”) refers to a number of eastern Algonquian nations — and to the special forests across Wabanakik that they call home.

In the 1600s, five nations— the Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Wolastoqiyik, and Mi’kmaq Peoples—formed a political union known as The Wabanaki Confederacy. First established to better protect communities from Iroquois and later European encroachment, today a primary goal of the Wabanaki Confederacy is to assert the ancestral jurisdictions of the Wabanaki Peoples, including traditional use and protection of the Wabanaki Forest.

Language & Land

As the name Wabanaki itself demonstrates, Indigenous languages are closely connected to the land and to place. These deeply rooted relationships are part of many Indigenous worldviews of care and stewardship for the land — relationships that have allowed forests and communities to thrive for thousands of years. The diversity and depth of Indigenous worldviews, relationships, and responsibilities to the land are best articulated through Indigenous language. In fact, when Indigenous languages are revitalized, so too is the diversity of life on the land.

“Indigenous languages are like ecological encyclopedias and ancestral guides with profound knowledge cultivated over centuries. If these languages are not passed on, then this wisdom is lost to humanity and the generations to come.”

Chiblow & Meighan, Language is land, land is language.

At a time when less than 1% of the pre-colonial Wabanaki forest remains intact, Indigenous languages may be key for protecting and restoring this unique forest. We invite you to refer to the Wabanaki forest by its original name—and to join us as we share and learn the local Wolastoqiyik and Mi’kmaq names for its many trees, animals, and plant life.

Keep Learning

Language represents only a fraction of the work that needs to be done. That is why we continue to unlearn and interrogate concepts of land “ownership” and what it means to steward the forests in our care — and how we can explore further land-based reconciliation, including opportunities for co-management or returning land to Indigenous nations.

To explore further, you can use this interactive map to learn whose traditional territories you live on, what languages are spoken there, and what treaties apply to your area. You can also read more about Reclaiming Indigenous Place Names and listen to Voices from the Land: Indigenous Peoples Talk Language Revitalization.

Sources

- Chiblow, S., & Meighan, P. J. (2021). Language is land, land is language: The importance of Indigenous languages. Human Geography.

- Roache, T. (2014, August 11). Wabanaki Confederacy: ‘We’re not dead, our fires are still burning strong’. APTN National News.

- Sutherland, M. (2021, June 25). Eel Ground First Nation forester makes a surprise appearance at pesticide hearings. CBC News.

- The map of traditional Wabanaki Territory is from Native Land, and Wabanakik translations are from the Wabanaki Collective.