Being People of the Dawn-Land

By shalan joudry, Posted on June 29, 2023

In Wapna’ki, we are the first to welcome the morning sun each day before the rest of Turtle Island (North America). We are first to give thanks to the new day. What does that mean to me when i look around this landscape as the sun rises?

It is the geography of the landscape that i want to begin with now: the mountains and valleys, the inlets of coasts and topography that have all shaped the way the rivers and waters flow, which have in turn shaped/influenced the very socio-political-economic systems of our Indigenous ancestors of Wapna’ki. From the soil that nourishes plant life to the waters and air, and of course, the very sunlight that nourishes the plants and animals who made this landscape their home. We wouldn’t be here without these basic elements. Whichever spiritual faith each person follows, can we agree that we also would not exist without the land to sustain us?

It is challenging for me to visualize how these very landscapes and waterways looked like 11,000-13,000 years ago when our first human ancestors began their story here. With the collective knowledges of Elders, historians and ecologists, organizations have put together images and stories of these millennia.

These landscapes were different 11,000 years ago, with some still covered in ice, some birthing grasslands and then the coming of more plants and animals. i imagine how the ancient ancestors must have travelled, harvested food, and made villages in a different way in those early generations here. Our very cultures, languages, and ways of being all came into existence or adapted with these ecosystems.

In biology classes in university i was not taught about the human involvement in the shaping of ecosystems through the millennia here, it was in fact the Elders and cultural leaders who taught me about that. The ancient ancestors were influenced by the incoming flora and fauna, and by the shape of the lands and waterways themselves. These impacted how those of long ago travelled, and settled, what was enough resources and how they related to one another. The people chose what to make their houses out of, and which animals and plants to help perpetuate for food, materials, medicines and more. The people created areas of higher-than-natural fertilizer (like human compost piles, whereby creating ecosystems better suited for the growth of nutrient-dependent plants and trees like Black Ash). The people also chose when and where to use fire on the land, like maintaining grassy areas along the coast for village sites or keeping some troublesome insect populations down. More research has taken place in BC with similar questions about the types of food and material plants close to village sites, as well as the nutrient-rich soils caused by human compost piles.

Transplanting and propagating certain food or material plants were common practices, but when not grown as a cleared area of gardens, these forest permaculture traditions were not as remarkable to newcomers as the corns, beans and squash of the nations west of Wapna’ki. An example of a species of plant that the ancestral Mi’kmaq propagated for forest gardens was sipekn / (one type of “wild potato” or also called “ground nut”). Another example of living as part of an ecosystem was the relationship with harvesting welima’ji’kewe’l (sweetgrass). As Robin Wall Kimmerer speaks about in “Braiding Sweetgrass”, because grasses typically respond well to some soil disturbance, the people carefully harvesting this grass each summer actually promotes more growth for the next season.

Braided sweetgrass. Photo by Nancy J. Turner

That interdependence formed human-nature specific ecosystems over time. The land grew diverse with changing climates and our ancient ancestors adapted and changed, as well. The ecosystems continued to influence settlements and social, economic and political relationships.

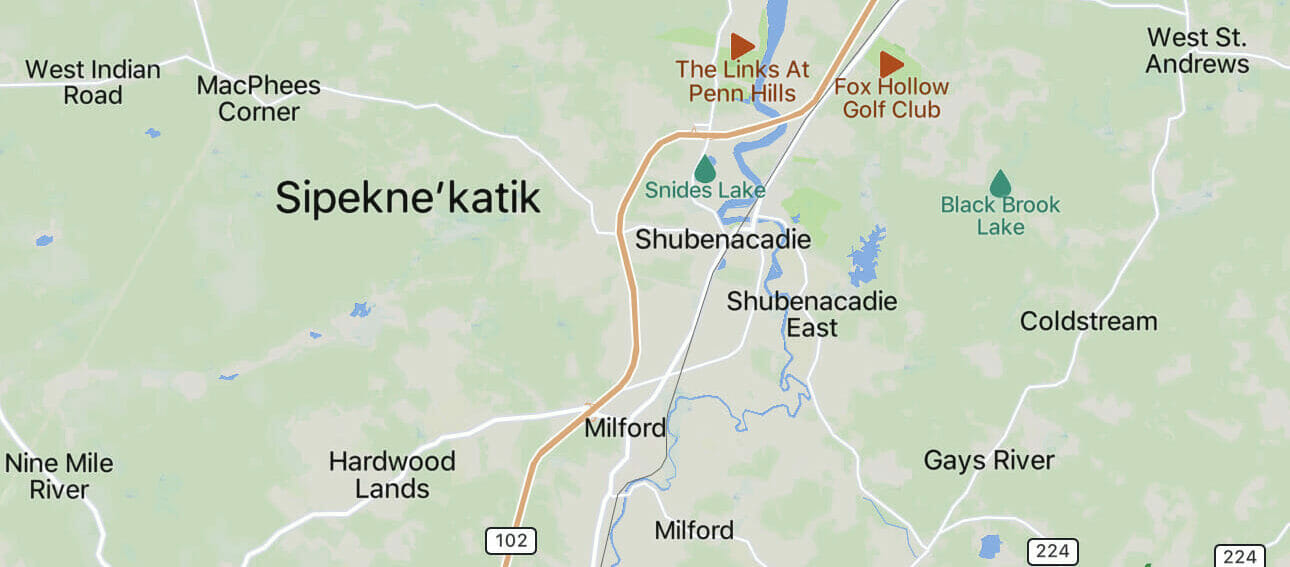

Our ancestors even named certain places on the land by what plant or animal was abundant there. In Mi’kma’ki, (land of the Mi’kmaq) the suffix -e’kati denotes “place of” and you can see some examples in Nova Scotia. Zoom in and take a look around using this interactive map.

![[Note: the added ‘k’ at the very end of the place name on the map means “at”].](https://forestsinternational.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/3-e1688046850933.png) A few examples close to my home are: Mikjikjue’kati (“place of turtles”) later renamed Lake Mulgrave in English; Sikunme’kati (“place of gaspereaux”) where we now see South Milford; Apji’jkmujue’kati (“place of the ducks”) instead of Cornwallis; and many more. Perhaps the most famous Mi’kmaw place name based on this form is Shubenacadie. The Mi’kmaw word is more accurately written: Sikipne’kati / Sipekne’kati (“place of groundnuts”).

A few examples close to my home are: Mikjikjue’kati (“place of turtles”) later renamed Lake Mulgrave in English; Sikunme’kati (“place of gaspereaux”) where we now see South Milford; Apji’jkmujue’kati (“place of the ducks”) instead of Cornwallis; and many more. Perhaps the most famous Mi’kmaw place name based on this form is Shubenacadie. The Mi’kmaw word is more accurately written: Sikipne’kati / Sipekne’kati (“place of groundnuts”).

Sipekne’katik, which means “where the wild potatoes grow”, is home to the Sipekne’katik First Nation.

Even if those thousands of years of change and adaptation feels incredibly distant, to an oral culture people, we still feel closely connected to those landscapes and ancestors. Some of the stories, songs, and dances that our cultural carriers pass on today come from thousands of years ago. And like all cultures, our ancestral ways shifted through the millennia, integrating newer ideas, visions, species, events, or trades with other nations. It was taught to me that the nations who make up the Wapna’ki Confederacy are our distant relatives and long-standing allies. It is no surprise that we have similarities in our languages and cultural practices. We must remember that the landscapes helped shape these nations and then these cultures helped shape these ecosystems. When the ecologists and biologists compiled data decades ago and noticed a commonality in the Eastern region of North America, calling it the “Acadian Forest” type, what they were noticing was in fact our region of family and allyship.

You see, as the French first settled here in Mi’kma’ki, making new allies with the Mi’kmaq, our ancestors would have given notice to the rest of the Wapna’ki region that these new settlers (having become the “Acadians”) were to be seen as allies in the region overall. This is how i understand why the Wapna’ki region fits with the Acadian forest type. The non-Indigenous ecologists recognized the French names of villages but did not recognize Indigenous nations. If they had, the ecologists would have called it the Wapna’ki Forest region from the beginning.

Note: Even though history says that the word, Acadie comes from the word, Arcadia, Mi’kmaw linguists suggest it comes more directly from our word part, “e’kati”. (The Mi’kmaw pronunciation sounds like “ay-gah-dee). The Mi’kmaq would have called the location of an Acadian settlement something that would translate as, “wenuj-e’kati”. “Place of the French”. That they adopted the term E’kati = Acadie. If this is the case, then “Acadian Forest” is almost fully what we would call it. We are simply missing the “Wapn”.

Photo by Dan Froese.

When we stand on these Wapna’ki landscapes today, let us give thanks to not only nature that has been shaped over the millennia, but also to the human ancestors who learned from these places, grew languages out of these ecosystems, and took care of these natural systems so that it made it possible for us to be here today.

We are still part of these ecosystems today. We separate ourselves daily, but it is our responsibility to see ourselves as part of the land.

We still need to feel that ground under our feet to remind us; we still need to be able to walk through some of those dynamic and old forests with complex fungi and a diversity of birds singing; we still need to be able to walk along riverbanks and see the natural fish species jumping; we still need the land/water in a deeply human way.

What can we do today that feels positive towards the land? As a Mi’kmaw, i would say that i should take seeds of natural plants in the forest and help propagate them into better or much-needed locations for it. An example is that Indigenous ecological organizations are working to re-seed and redistribute culturally important species that belong to our diverse ecosystem, like Wisqoq, Black Ash.

Being a positive active part of the land includes every time that we can help cover up reptile eggs/nests to keep predators out, give organic carbon back when we harvest food/materials out of the forest, and plant pollinator-loving plants. Other contemporary ways of caring for nature as humans are also picking up litter and transporting garbage out of natural landscapes, or the way we advocate for green areas in and around the urban centres. Even as complex ecosystems sustain humans, we must find ways to co-exist.

As the sun rose on the longest daylight last week, and as i watch the sun rise each morning, i give thanks for the new chance to do the best with my hands, mind, and heart as humans have carried out for millennia. Now it’s our turn.

shalan joudry is a L’nu (Mi’kmaw) poet, storyteller, podcast producer, playwright, actor and singer. She is also an ecologist and cultural interpreter. shalan uses Two-eyed Seeing methodologies to ground mainstream ecologists into L’nu cultural perspectives to work more effectively together.