Towards Indigenous Reconciliation

By Mia Tran, Posted on November 11, 2021

In Canada and across the globe, there is increasing recognition of Indigenous leadership as essential to both the environmental movement and the interconnected demands for Truth and Reconciliation. In this second blog of the Environmental Justice series, we explore further the connection between environmental justice, forests, and reconciliation.

Patterns of Injustice

The costs of environmental degradation are often distributed inequitably to communities of colour. This pattern is termed environmental racism and impacts First Nations, Inuit, and Metis Peoples across Turtle Island—including Canada.

The Aajimwnaang Resource Centre borders a chemical plant. Photo by: The Kurgan

In Chemical Valley, Ontario, Aamjiwnaang First Nations have fought for over a decade against the toxic effects from the numerous chemical plants and oil refineries that sit just outside of their community. In New Brunswick, the Mi’kmaq community in Elsipogtog First Nation recently erected a blockade to express their concerns over a proposed shale-gas project and the lack of consultation about development on their traditional land. These two stories exemplify patterns of environmental injustice– and of Indigenous communities leading movements against injustice and for the right to a healthy environment.

Towards Land-Based Reconciliation

“Reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians, from an Aboriginal perspective, also requires reconciliation with the natural world. If human beings resolve problems between themselves but continue to destroy the natural world, then reconciliation remains incomplete.”

— Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Colonization often includes the dispossession of Indigenous peoples from their lands. Advocates for Land Back argue that land-based reconciliation means acknowledging this historic and ongoing colonization of the land, recognizing Indigenous sovereignty and the ability to govern as sovereign nations, and uplifting Indigenous worldviews of land stewardship and protection.

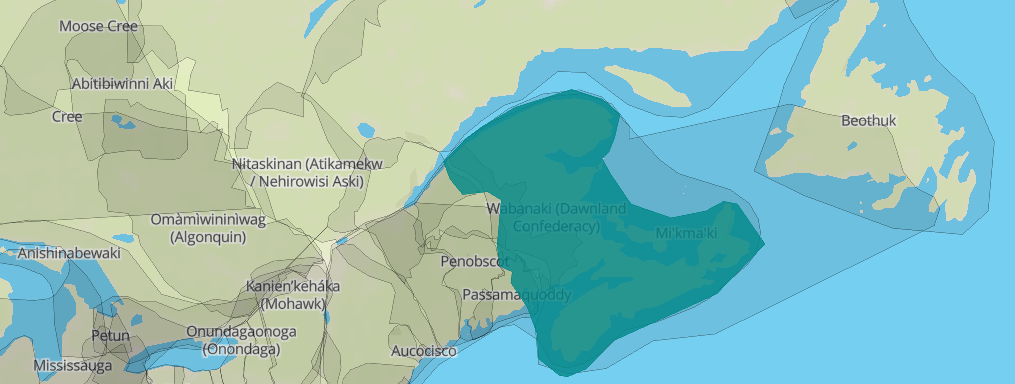

In eastern Canada, the land is covered by the Treaties of Peace and Friendship signed by the British Crown and Wolastoqiyik and Mi’kmaq Peoples in 1725. The treaties did not deal with the surrender of lands and resources but instead recognized Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik title and established the rules for what was to be an ongoing relationship between nations.

Lands covered by the Peace and Friendship Treaties. Map created by Native Land Digital / Native-Land.ca

In practice, Canada’s implementation of the treaties has frequently failed to honour Indigenous sovereignty or rights—limiting Indigenous communities access, use, and stewardship of the land. This not only affects Indigenous livelihoods and ways of living but also contributes to the erasure of culture and identity.

At Community Forests International, we understand that the colonial land governance systems must change to recognize and uphold Indigenous rights if we are to successfully protect and restore the forests and other natural ecosystems. Alongside and in solidarity with Indigenous partners such as the Wolostequey Nation in New Brunswick and The Ulnooweg Development Group, we work towards amplifying Indigenous rights and strengthening understanding and allyship between Indigenous and settler forestry practitioners around issues of forest care and climate action.

Ways you can do to support land-based reconciliation:

- Read more about Indigenous Rights and Private Land Conservation.

- Search this interactive map to learn which Indigenous groups’ traditional territories you live on, what languages have been spoken there, and what treaties apply to your area.

- Read “Whose Land Is It Anyway? A Manual For Decolonization” by Peter McFarlane and Nicole Schabus.

- Browse the Think Indigenous podcast and enjoy an episode.

- Read the YellowHead Institute’s Home – Land Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper

What’s next?

While environmental justice was first made famous in the fight against toxics and hazardous waste, today, the environmental justice movement has grown to recognize the disproportionate impact of the climate crisis on all marginalized communities and is continually evolving to recognize the intersectionality of all forms of oppression in the fight for a healthy, safe and sustainable environment.

Stay tuned for the next blog in the Environmental Justice series, featuring an interview with environmental activist Tina Oh.

About the author: Mia Tran is an environmental studies student at Mount Allison University, with minors in political science and geography. Originally from Hanoi, Vietnam, Mia has lived in Charlottetown, PEI since 2017. Mia was Community Forests International’s Climate Justice summer intern in 2021.