What is Environmental Justice?

By Mia Tran, Posted on November 4, 2021

Environmental issues affect all of us — but not all of us equally. Marginalized groups and communities face disproportionate impacts of the climate crisis — while being the least responsible for its causes. Yet for as long as environmental harms and impacts have been made, environmental activists and communities have fought back. Today, that movement is referred to as “environmental justice”.

In this first blog of the Environmental Justice series, we look at the history of environmental justice and environmental racism.

What is Environmental Justice?

Environmental justice seeks to recognize and address inequalities of environmental harm by examining environmental concerns through a social lens. What started as a movement against toxics in racialized communities, environmental justice has become the heart of most environmental movements today.

“Environmental justice is the principle that all people are entitled to equal environmental protection regardless of race, colour or national origin. It’s the right to live and work and play in a clean environment.”

— Dr Robert Bullard

A Glance Back

One of the most famous environmental movements took place in the small, Black farming community of Warren County, North Carolina. In the 1980s, the state voted to place a hazardous waste landfill in the community. When the news reached the community, protests broke out against the decision.

Protestors led by Reverend Joseph Lowery march against a proposed toxic waste dump in Warren County, North Carolina, in October 1982. Photo: Bettman/Getty Images

These protests would last over six weeks—and bring together people from other low-income and minority communities across the country. Protestors drew national attention to racial disparities in environmental protection and the human right to a healthy environment. Sadly, the people of Warren County ultimately lost against the state—but their story is often told as the origins of environmental justice in North America.

Understanding Environmental Racism

Benjamin Chavis, a Black civil rights activist, saw Warren County as a clear example of racial inequalities of environmental hazards. Chavis defined this pattern as environmental racism: “racial discrimination in environmental policy-making, the enforcement of regulations and laws, the deliberate targeting of communities of colour and exclusion of people of colour from leadership in the environmental movement.”

Since Chavis, increasing research from across the globe shows what Black, Indigenous, and other communities of colour have known and vocalized for decades: environmental harms have historically and continue to disproportionately affect communities of colour.

“There exists a pattern in Canada whereby marginalized groups, and Indigenous peoples, in particular, find themselves on the wrong side of a toxic divide, subject to conditions that would not be acceptable in respect of other groups in Canada.”

— Baskut Tuncak, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Toxics, 2019

Across Canada, patterns of environmental racism are evident. Toxic dumps, pipelines, and other high-risk projects are more likely to be placed near communities of colour, while these same communities enjoy vastly fewer environmental benefits like green spaces and tree cover. In addition, these communities often lack the political power to fight back against harmful decisions, projects, or policies.

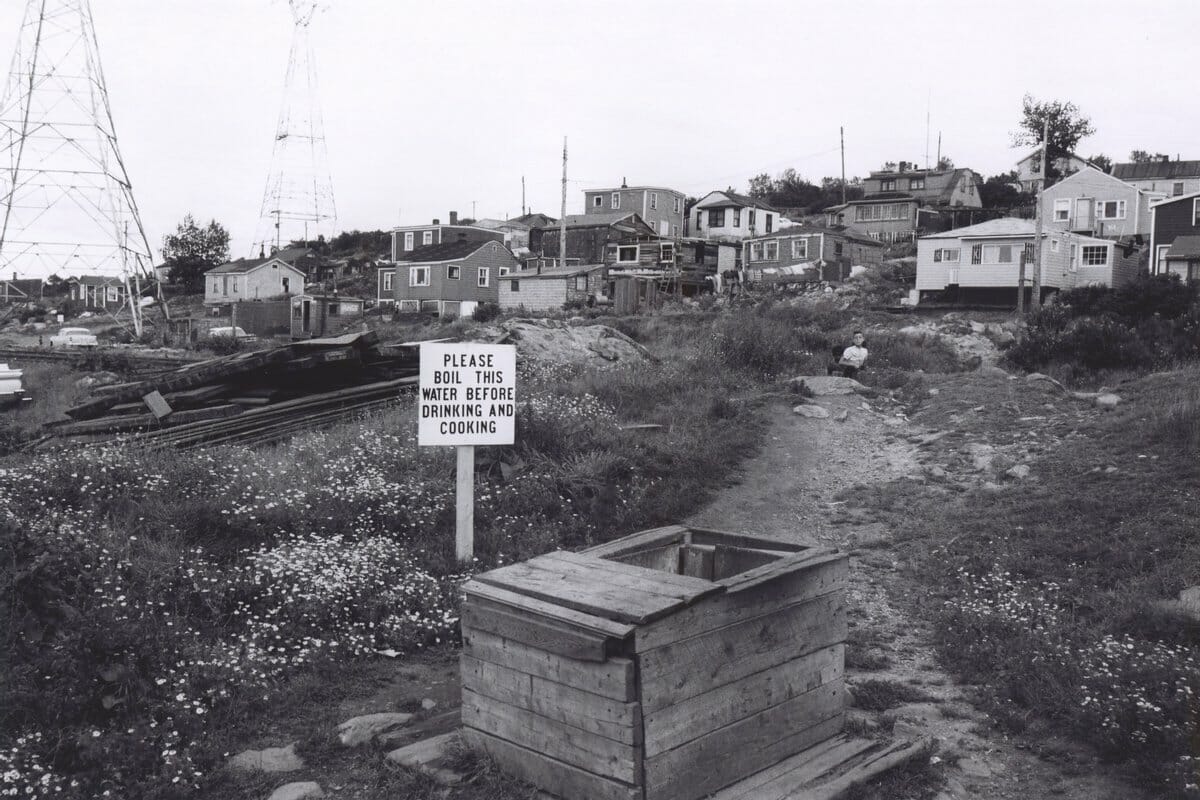

A well-known example is Africville, Nova Scotia. Africville was a Black community that, amongst other injustices, became a regional dumping ground for Halifax’s toxic and medical waste in the 1950s—despite the City publicly recognizing these toxic dumps as a “health menace”.

Africville residents did not receive water and sewer services. For their water supply, they relied upon an assortment of wells. Photo: Nova Scotia Archives, Bob Brooks.

The City of Halifax continued to place hazardous and polluting services in Africville, including a fertilizer plant, slaughterhouses, and the “night-soil disposal pits”. After decades of denying requests for basic services such as running water, the city designated Africville a slum, forcibly relocated the residents, and destroyed the town in 1970. Today, many former residents are continuing to seek compensation—and justice—for what they suffered.

A Movement For Justice

In June of 2021, Canadian Member of Parliament Lenore Zann introduced Bill C-230: The National Strategy Respecting Environmental Racism and Environmental Justice Act. If the bill passes, it will urge the federal government to redress environmental racism. This includes identifying, documenting and monitoring environmental racism; creating processes to increase participation of Indigenous and racialized communities in the environmental policy-making process; and working to ensure affected communities have access to clean air and water.

In the next blog of the Environmental Justice series, take a look at how Indigenous-led environmental action is needed for environmental justice and reconciliation.

About the author: Mia Tran is an environmental studies student at Mount Allison University, with minors in political science and geography. Originally from Hanoi, Vietnam, Mia has lived in Charlottetown, PEI since 2017. Mia was Community Forests International’s Climate Justice summer intern in 2021.

Our Commitment

At Community Forests International, we know that dismantling the underlying inequalities in our society is critical to building a resilient environmental movement. Justice and equality are fundamental for people to be the restorative force that the world needs—and Community Forests International is committed to centring anti-racism in our organization, mission, and actions.